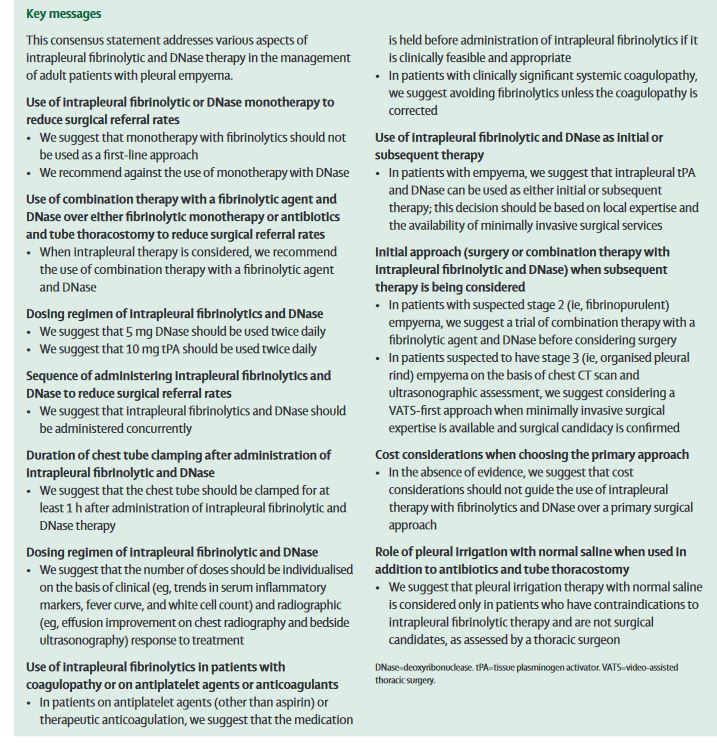

“Parapneumonic effusions evolve through a spectrum of three stages. The initial exudative stage (stage 1; analogous to simple parapneumonic effusion) is characterised by an increased outpouring of fluid into the pleural space mediated by capillary permeability. If left

untreated, persistent inflammation with the associated rise in fluid plasminogen activator inhibitor causes a decrease in fluid fibrinolytic concentrations. During this second stage (stage 2; fibrinopurulent stage), as the effusion becomes infected, septations and adhesions

induced by fibrin deposition divide the space into pockets or locules. With the proliferation of fibroblasts and the formation of a pleural peel, lung expansion becomes restricted and can result in a non-expandable lung. It is important to initiate all medical treatment before this

final so-called organising stage (stage 3) ensues.”