One discussion this week included open versus closed hemorrhoidectomy.

Reference: Bhatti M, Sajid MS, Baig MK. Milligan-Morgan (open) versus Ferguson haemorrhoidectomy (closed): A systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized, controlled trails. World Journal of Surgery. 2016 Jun;40(6):1509-1519. doi:10.1007/s00268-016-3419-z.

Summary: In Europe, the Milligan-Morgan procedure or open haemorrhoidectomy (OH) is more frequently practised, whereas in the United States of America the closed haemorrhoidectomy (CH) procedure, as described by Ferguson and Heaton, is the most popular. CH is purported to be a less painful procedure and associated with faster wound healing due to primary wound closure. However, the conflicting outcomes following both procedures have been debated in the published literature and several controversies around post-operative pain still need clarification.

Relevant prospective randomized, controlled trials (irrespective of type, language, gender, blinding, sample size or publication status) on CH versus OH for the management of HD until May 2014 were included in this review.

Ultimately, 11 RCTs encompassing 1326 patients were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Significant heterogeneity was found among included trials.

CONCLUSIONS: Variables of pain on defecation, length of hospital stay, post-operative complications, HD recurrence and risk of surgical site infection were similar in both groups.

Based upon the findings of this review, CH was associated with a reduced post-operative pain, faster wound healing, lesser risk of post-operative bleeding but prolonged duration of operation.

Findings of this review are contradictory to a 2007 meta-analysis of six randomized, controlled trials.

To view full data analyses (3 tables and 11 figures!) click on the link in the reference at the top of this post.

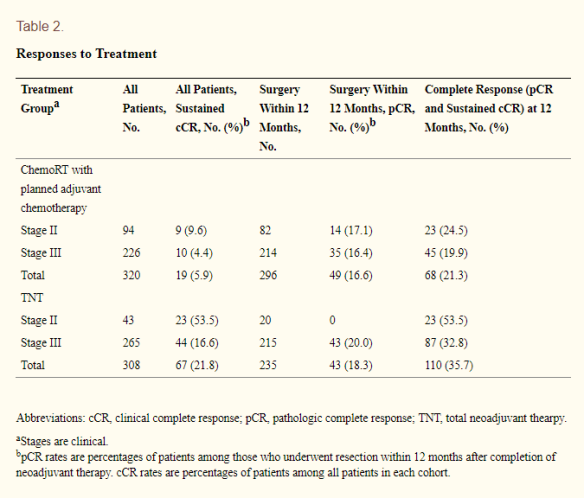

(Cerek et al, 2018)

(Cerek et al, 2018)