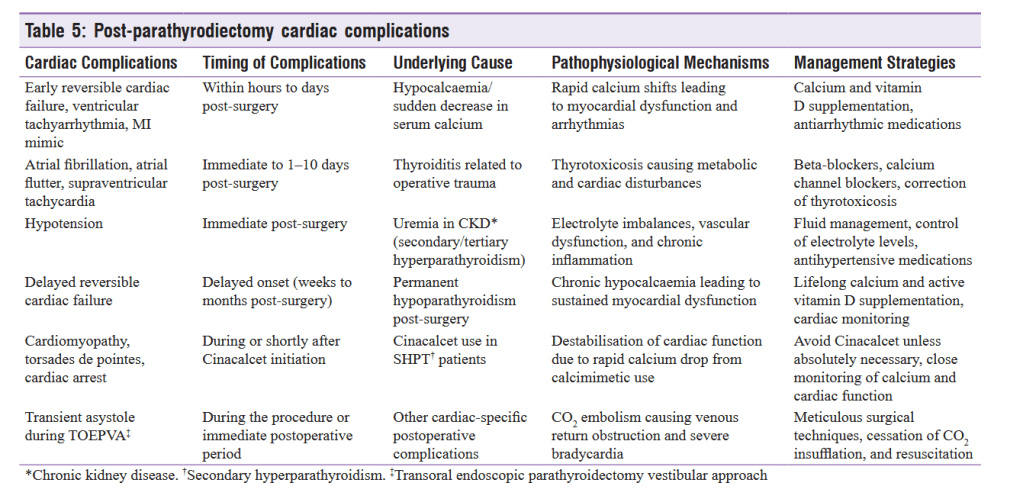

“Parathyroidectomy (PTX) is primarily performed to treat primary and secondary hyperparathyroidism (HPT) and has been shown to reduce cardiac risk factors, including ECG abnormalities, 2D-echo abnormalities, arrhythmias, and NT-proBNP levels Cardiac complications, though rare, can occur in patients undergoing thyroidectomy. In a US-based cohort of 3,575 patients, approximately 0.2%–0.3% developed congestive heart failure (CHF) during follow-up. A study by Kravietz et al. found that while readmission rates were lower in primary HPT (PHPT) patients (5.6%) compared to secondary HPT (SHPT) patients (19.4%), heart failure was more prevalent in PHPT patients (10.8%) compared to SHPT patients (3.9%). Additionally, patients with existing CHF undergoing PTX have a higher likelihood of readmission. Although cardiac complications are rare, they can occasionally be fatal.”