A discussion this week included adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer after neoadjuvant and surgery.

Reference: Breugom AJ, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for rectal cancer patients treated with preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy and total mesorectal excision: a Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) randomized phase III trial. Annals of Oncology. 2015 Apr;26(4):696-701. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu560.

Summary: Locoregional recurrence rates and survival have significantly

improved with the introduction of total mesorectal excision (TME) for patients with rectal cancer. The addition of preoperative radiotherapy to TME surgery resulted in a more than 50% decrease in locoregional recurrences. However, the combination of preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy and TME surgery did not improve overall or disease-free survival. Up to 30% of all patients treated with curative intent for localized rectal cancer will develop distant metastases, and distant metastases are still the main cause

of death after rectal cancer.

A multicentre, randomized phase III trial, PROCTOR-SCRIPT, was conducted to investigate the value of adjuvant chemotherapy with fluoropyrimidine monotherapy after preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy and TME surgery. The primary outcome was overall survival. Secondary outcomes were disease-free survival, overall recurrence rate, and locoregional and distant recurrence rate separately.

METHODS: Patients from 52 hospitals were recruited. Those with histologically proven stage II or III rectal adenocarcinoma were randomly assigned to observation (n=221) or adjuvant chemotherapy (n=216) after preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy and TME. Radiotherapy consisted of 5 × 5 Gy. Chemoradiotherapy consisted of 25 × 1.8-2 Gy combined with 5-FU-based chemotherapy. Adjuvant chemotherapy consisted of 5-FU/LV (PROCTOR) or eight courses capecitabine (SCRIPT). Randomization was based on permuted blocks of six, stratified according to centre, residual tumour, time between last irradiation and surgery, and preoperative treatment. The primary end point was overall survival.

RESULTS: Between 1 March 2000 and 1 January 2013, 470 patients were included, of whom 33 were incorrectly randomized. Therefore, 437 patients (309 Dutch and 128 Swedish patients) were eligible for analyses. The trial was finally closed due to poor patient accrual without reaching the intended inclusion.

- Survival: A total of 95 patients died. Five-year overall survival was 79.2% in the observation group and 80.4% in the chemotherapy group.

- Disease-free survival: No statistically significant difference in disease-free survival was

observed. Five-year disease-free survival was 55.4% for the observation group and 62.7% for the chemotherapy group.

- Recurrences: In total, there were 157 recurrences. At 5 years, the cumulative incidence for overall recurrences was 40.3% in the observation group and 36.2% in the chemotherapy group.

- Locoregional recurrences: The 5-year cumulative incidence for locoregional recurrences was 7.8% in the observation group versus 7.8% in the chemotherapy group. This amounted to 38.5% and 34.7%, respectively, for distant recurrences.

CONCLUSION: The PROCTOR-SCRIPT trial could not demonstrate a significant benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy with fluoropyrimidine monotherapy regarding overall survival, disease-free survival, and recurrence rates after preoperative (chemo)radiotherapy and TME surgery in ypTNM stage II and III rectal cancer patients. However, this trial did not complete planned accrual.

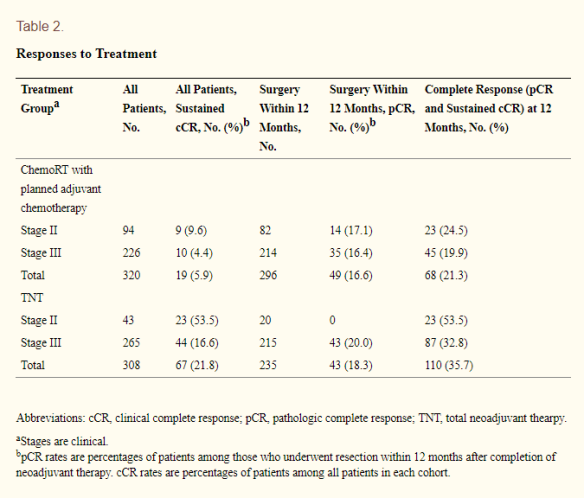

(Cerek et al, 2018)

(Cerek et al, 2018)