Keelan S, Flanagan M, Hill ADK. Evolving Trends in Surgical Management of Breast Cancer: An Analysis of 30 Years of Practice Changing Papers. Front Oncol. 2021 Aug 4;11:622621. Free full-text.

Keelan S, Flanagan M, Hill ADK. Evolving Trends in Surgical Management of Breast Cancer: An Analysis of 30 Years of Practice Changing Papers. Front Oncol. 2021 Aug 4;11:622621. Free full-text.

Shackford SR. (2018). Venous Disease. In: Abernathy’s Surgical Secrets, 7th ed.: p. 357.

What is the difference between phlegmasia alba dolens and phlegmasia cerulea dolens?

“These two entities occur following iliofemoral venous thrombosis, 75% of which occur on the left side presumably because of compression of the left common iliac vein by the overlying right common iliac artery (May-Thurner syndrome). Iliofemoral venous thrombosis is characterized by unilateral pain and edema of an entire lower extremity, discoloration, and groin tenderness. In phlegmasia alba dolens (literally, painful white swelling), the leg becomes pale. Arterial pulses remain normal. Progressive thrombosis may occur with propagation proximally or distally and into neighboring tributaries. The entire leg becomes both edematous and mottled or cyanotic. This stage is called phlegmasia cerulea dolens (literally, painful purple swelling). When venous outflow is seriously impeded, arterial inflow may be reduced secondarily by as much as 30%. Limb loss is a serious concern and aggressive management (i.e., venous thrombectomy, catheter-directed lytic therapy, or both) is necessary.”

Chinsakchai K, et al. Trends in management of phlegmasia cerulea dolens. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2011 Jan;45(1):5-14. Full-text for Emory users.

Bryski MG, et al. Techniques for intraoperative evaluation of bowel viability in mesenteric ischemia: A review. Am J Surg. 2020 Aug;220(2):309-315. Full-text for Emory users.

“Comparison studies in animal models and clinical experience featuring fluorescein flowmetry have consistently demonstrated the superiority of dye-based perfusion monitoring for intraoperative bowel assessment as compared to standard clinical criteria, DUS, and pulse oximetry/PPG. (45,46,47,53,54) However, these results are not universal, with some large animal models demonstrating no difference between fluorescein, DUS, and PPG, and an additional study showing that DUS actually outperforms fluorescein for intraoperative bowel assessment. (13,18,43)” (p. 312)

Continue readingAmr MA, et al. Endoscopy in the early postoperative setting after primary gastrointestinal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014 Nov;18(11):1911-6. Full-text for Emory users.

Methods: Review of patients from 2002 to 2013 who underwent flexible endoscopy within 6 weeks of creation of gastrointestinal anastomosis. Exclusion criteria included intraoperative endoscopy, anastomotic perforation prior to endoscopy, and endoscopy remote from the anastomotic site. Data are presented as median (interquartile range; IQR) or percentages as appropriate.

Continue reading“Pneumobilia should be differentiated from portal venous gas. Portal venous gas is peripherally distributed to within 2 cm of the liver margin, whereas pneumobilia is centrally distributed.” (Gupta, P, et al. “PLAIN FILMS: BASICS.” Acute Care Surgery: Imaging Essentials for Rapid Diagnosis Eds. Kathryn L. Butler, et al. McGraw Hill, 2015.)

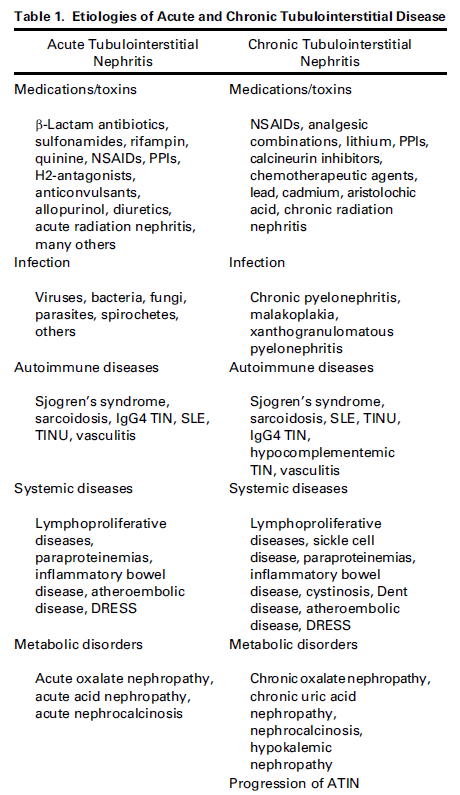

Continue readingPerazella MA. Clinical Approach to Diagnosing Acute and Chronic Tubulointerstitial Disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017 Mar;24(2):57-63. Full-text for Emory users.

Ferreira GF, et al. Parathyroidectomy after kidney transplantation: short-and long-term impact on renal function. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66(3):431-5. Free full-text.

Materials and methods: This was a retrospective case-controlled study. Nineteen patients with persistent hyperparathyroidism underwent parathyroidectomy due to hypercalcemia. The control group included 19 patients undergoing various general and urological operations.

Results: In the parathyroidectomy group, a significant increase in serum creatinine from 1.58 to 2.29 mg/dl (P < 0.05) was noted within the first 5 days after parathyroidectomy. In the control group, a statistically insignificant increase in serum creatinine from 1.49 to 1.65 mg/dl occurred over the same time period. The long-term mean serum creatinine level was not statistically different from baseline either in the parathyroidectomy group (final follow-up creatinine = 1.91 mg/dL) or in the non-parathyroidectomy group (final follow-up creatinine = 1.72 mg/dL).

Conclusion: Although renal function deteriorates in the acute period following parathyroidectomy, long-term stabilization occurs, with renal function similar to both preoperative function and to a control group of kidney-transplanted patients who underwent other general surgical operations by the final follow up.

Continue reading