“In recent years, indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence imaging has emerged as an alternative tool to enhance the visualization of biliary structures during LC. ICG is a fluorescent dye that, when injected intravenously, is preferentially taken up by the liver and excreted into the bile ducts. When exposed to near-infrared light, ICG causes the biliary structures, such as the CD, CBD, and CA, to fluoresce, making them more distinguishable from surrounding tissues thereby facilitating real-time visualization of biliary structures during the dissection of Calot’s triangle. The timing of ICG injection is critical to ensure that the biliary anatomy lights up distinctly without interference from non-biliary structures.

However, the routine use of ICG fluorescence imaging in LC has not yet been standardized, and there is ongoing debate about whether its widespread adoption would significantly reduce the incidence of BDI and improve patient outcomes. This systematic review aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the efficacy and safety of ICG fluorescence imaging in LC, specifically comparing its impact on the incidence of BDI to that of conventional white light (WL) imaging.”

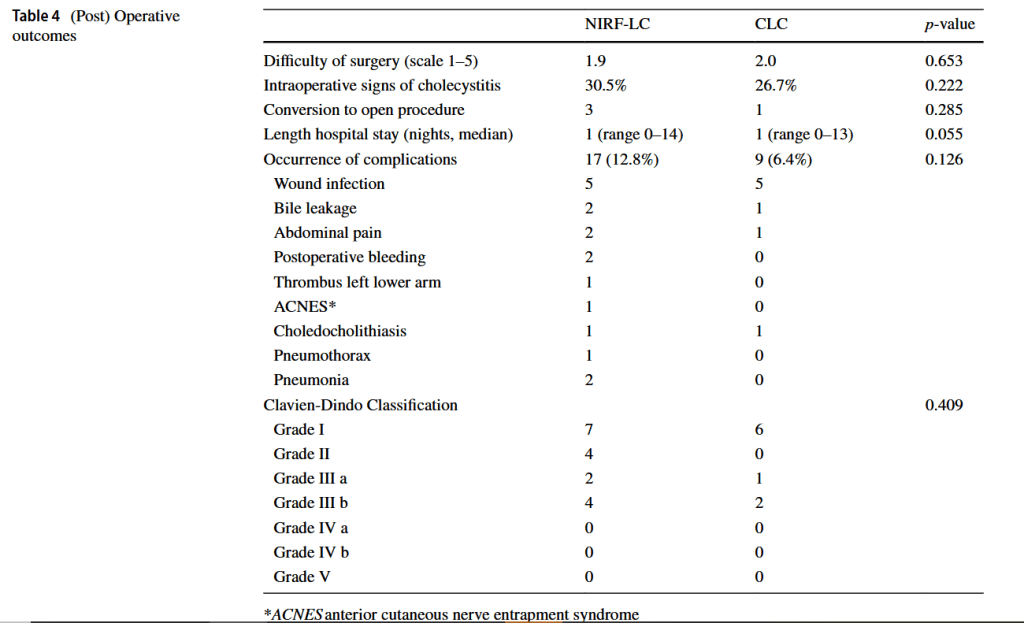

Table 4. Comparison of visualization of biliary structures and incidence of BDI using ICG fluorescence vs WL in LC.

BDI, bile duct injury; CBD, common bile duct; CD, cystic duct; CHD, common hepatic duct; ICG, indocyanine green; LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy; WL, white light; -, not specified

| Author(s) and year | Visualization of CD | Visualization of CBD | Visualization of CHD | Visualization of the CD-CBD junction | Incidence of BDI using ICG | Incidence of BDI using WL |

| Symeonidis et al., 2024 | No significant difference (p = 0.225) | No significant difference (p = 0.276) | No significant difference (p = 0.940) | No significant difference (p = 0.827) | 0 | 0 |

| Ma et al., 2023 | Before dissecting Calot’s: no significant difference (p = 0.075). After dissecting Calot’s: ICG signifi-cantly improved visualization (p = 0.02) | Before dissecting Calot’s: no significant difference (p = 0.075). After dissecting Calot’s: ICG signifi-cantly improved visualization (p = 0.02) | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| Xu et al., 2023 | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| Stolz et al., 2023 | No significant difference | No significant difference | No significant difference | No significant difference | – | – |

| Lie et al., 2023 | Improved RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.07–1.43, p = 0.003 | Improved: RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.07–1.60, p = 0.009 | – | – | No significant difference: (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.07–1.58, p = 0.17) | No significant difference: (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.07–1.58, p = 0.17) |

| Losurdo et al., 2022 | – | – | – | – | 0 | 1.4%, p = 0.728 |

| Lacuzzo et al., 2022 | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| Jin et al., 2022 | – | – | – | – | 0 | 1.83%, p = 0.389 |

| Lim et al., 2021 | No significant difference: RR = 0.90, p = 0.12, 95% CI 0.79– 1.03, I² = 74% | No significant difference: RR = 0.82, p = 0.09, 95% CI 0.65– 1.03, I² = 87% | ICG significantly improved visualization: RR = 0.58, p = 0.03, 95% CI 0.35–0.93, I² = 91% | No significant difference: RR = 0.68, p = 0.06, 95% CI 0.45– 1.02, I² = 94% | 0 | 2 (0.55%) |

| Dip et al., 2021 | – | – | – | – | 1 (0.06%) | 12 (0.25%) |

| Broderick et al., 2021 | – | – | – | – | 0 | 1 (0.1%), p = 1 |

| Keeratibharat, 2021 | ICG signifi-cantly improved visualization, p = 0.001 | ICG signifi-cantly improved visualization, p = 0.002 | ICG signifi-cantly improved visualization, p = 0.000 | – | 0 | 0 |

| Ambe et al., 2019 | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0 |

| Dip et al., 2019 | Before dissecting Calot’s: ICG signifi-cantly improved visualization (p ≤ 0.001). After dissecting Calot’s: no significant difference (p = 0.83) | Before and after dissecting Calot’s: ICG signifi-cantly improved visualization (p < 0.001) | Before and after dissecting Calot’s: ICG signifi-cantly improved visualization (p < 0.001) | Before and after dissecting Calot’s: ICG signifi-cantly improved visualization (p < 0.001) | 0 | 2 (0.62%) |