Rechenmacher SJ, Fang JC. Bridging Anticoagulation: Primum Non Nocere. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Sep 22;66(12):1392-403.

Full-text for Emory users.

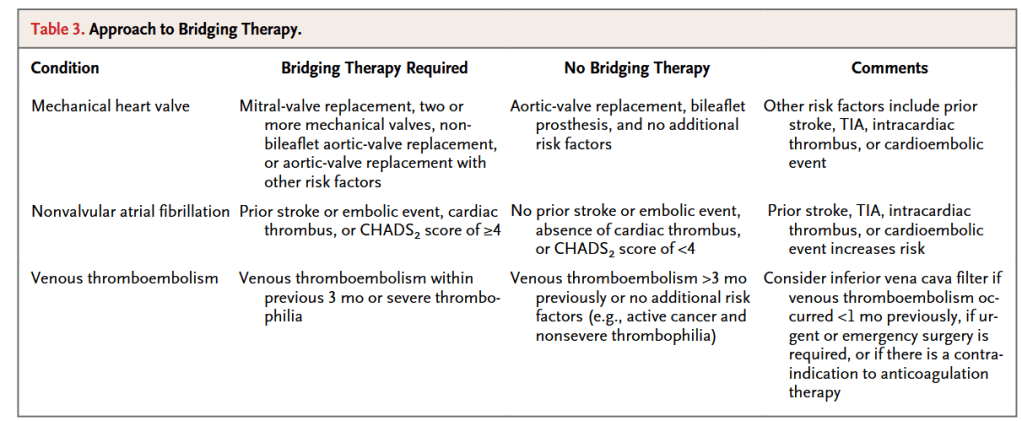

Conclusions: Periprocedural anticoagulation management is a common clinical dilemma with limited evidence (but 1 notable randomized trial) to guide our practices. Although bridging anticoagulation may be necessary for those patients at highest risk for TE, for most patients it produces excessive bleeding, longer length of hospital stay, and other significant morbidities, while providing no clear prevention of TE. Unfortunately, contemporary clinical practice, as noted in physician surveys, continues to favor interruption of OAC and the use of bridging anticoagulation. While awaiting the results of additional randomized trials, physicians should carefully reconsider the practice of routine bridging and whether periprocedural anticoagulation interruption is even necessary.

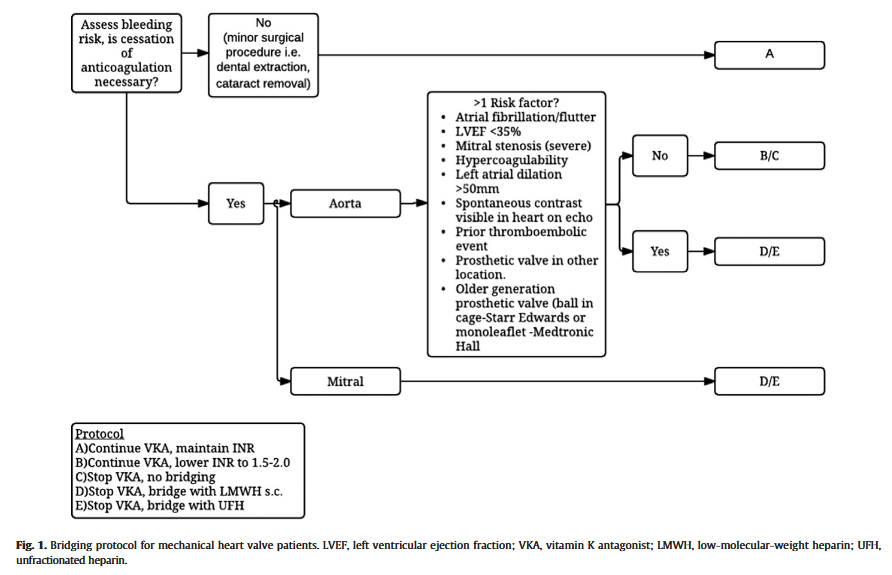

Central Illustration. Bridging Anticoagulation: Algorithms for Periprocedural Interrupting and Bridging Anticoagulation. Decision trees for periprocedural interruption of chronic oral anticoagulation (top) and for periprocedural bridging anticoagulation (bottom). OAC = oral anticoagulation.

Central Illustration. Bridging Anticoagulation: Algorithms for Periprocedural Interrupting and Bridging Anticoagulation. Decision trees for periprocedural interruption of chronic oral anticoagulation (top) and for periprocedural bridging anticoagulation (bottom). OAC = oral anticoagulation.

Continue reading →