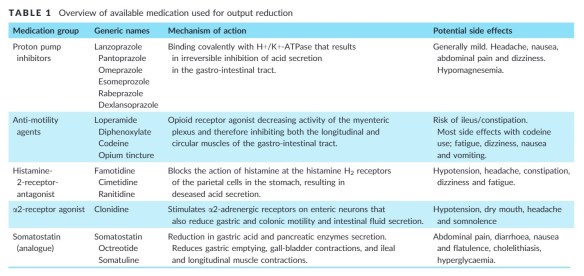

de Vries FEE, et al. Systematic review: pharmacotherapy for high-output enterostomies or enteral fistulas. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Aug;46(3):266-273.

Nutritional support of the enterocutaneous fistula patient

Kumpf VJ, et al. ASPEN-FELANPE Clinical Guidelines: Nutrition Support of Adult Patients With Enterocutaneous Fistula.JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2017 Jan;41(1):104-112. doi: 10.1177/0148607116680792.

Questions addressed in these guidelines:

In adult patients with enterocutaneous fistula: (1) What factors best describe nutrition status? (2) What is the preferred route of nutrition therapy (oral diet, enteral nutrition, or parenteral nutrition)? (3) What protein and energy intake provide best clinical outcomes? (4) Is fistuloclysis associated with better outcomes than standard care? (5) Are immune-enhancing formulas associated with better outcomes than standard formulas?(6) Does the use of somatostatin or somatostatin analogue provide better outcomes than standard medical therapy? (7) When is home parenteral nutrition support indicated?

Guidelines for the perioperative management of anticoagulants

One discussion this week focused on the perioperative management of NOACs.

Reference: DynaMed Plus [Internet]. Ipswich (MA): EBSCO Information Services. 1995 -. Record No. 227537, Periprocedural management of patients on long-term anticoagulation; [updated 2018 Oct 10, cited 2018 Oct 12; [about 26 screens]. Emory login required.

Summary: The information below is from DynaMed Plus (2018). To view full information on the topic, click on the citation above.

Vitamin K antagonists in patients undergoing major surgery or procedures

- Consider continuing vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy in patients who require minor dental procedures, minor dermatological procedures, or cataract surgery.

- In those having a minor dental procedure, consider coadministering an oral hemostatic agent or stopping the VKA 2 to 3 days before the procedure.

- In those undergoing implantation of a pacemaker or an implantable cardioverter device, consider continuing VKA therapy.

- In those having a major surgery or procedure, stop VKA therapy 5 days before surgery.

- Resume VKA therapy 12-24 hours after surgery when there is adequate hemostasis.

Bridging therapy in patients undergoing major surgery or procedures

- If at low risk for thrombosis, consider omitting bridging therapy.

- If at moderate risk for thrombosis, assess individual patient- and surgery-related factors when considering bridging therapy.

- If at high risk for thrombosis consider bridging therapy with unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH).

- For those receiving bridging therapy with UFH, stop UFH 4-6 hours before surgery.

- For those receiving bridging therapy with therapeutic-dose LMWH, stop LMWH 24 hours before surgery.

- For those receiving bridging therapy with UFH or therapeutic-dose LMWH and undergoing non-high-bleeding-risk surgery, consider resuming heparin 24 hours after surgery.

- For those receiving bridging therapy with UFH or therapeutic-dose LMWH and undergoing high-bleeding-risk surgery, consider resuming heparin 48-72 hours after surgery.

Prognostic factors in splanchnic vein thromboses

Ageno W, et al. Long-term Clinical Outcomes of Splanchnic Vein Thrombosis: Results of an International Registry. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sep;175(9):1474-80. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3184.

Full-text for Emory users.

RESULTS: Of the 604 patients (median age, 54 years; 62.6% males), 21 (3.5%) did not complete follow-up. The most common risk factors for SVT were liver cirrhosis (167 of 600 patients [27.8%]) and solid cancer (136 of 600 [22.7%]); the most common sites of thrombosis were the portal vein (465 of 604 [77.0%]) and the mesenteric veins (266 of 604 [44.0%]). Anticoagulation was administered to 465 patients in the entire cohort (77.0%) with a mean duration of 13.9 months; 175 of the anticoagulant group (37.6%) received parenteral treatment only, and 290 patients (62.4%) were receiving vitamin K antagonists. The incidence rates (reported with 95% CIs) were 3.8 per 100 patient-years (2.7-5.2) for major bleeding, 7.3 per 100 patient-years (5.8-9.3) for thrombotic events, and 10.3 per 100 patient-years (8.5-12.5) for all-cause mortality. During anticoagulant treatment, these rates were 3.9 per 100 patient-years (2.6-6.0) for major bleeding and 5.6 per 100 patient-years (3.9-8.0) for thrombotic events. After treatment discontinuation, rates were 1.0 per 100 patient-years (0.3-4.2) and 10.5 per 100 patient-years (6.8-16.3), respectively. The highest rates of major bleeding and thrombotic events during the whole study period were observed in patients with cirrhosis (10.0 per 100 patient-years [6.6-15.1] and 11.3 per 100 patient-years [7.7-16.8], respectively); the lowest rates were in patients with SVT secondary to transient risk factors (0.5 per 100 patient-years [0.1-3.7] and 3.2 per 100 patient-years [1.4-7.0], respectively).

Surgical Grand Rounds: Social Media in Surgical Education (January 16, 2020)

Presented by Andrew Morris, MD, Chief Resident

Department of Surgery, Emory University School of Medicine

Further readings and resources referenced in Dr. Morris’ presentation:

Appropriate/Responsible Social Media Interactions

ACS (2019). Statement on Guidelines for the Ethical Use of Social Media by Surgeons. Bull Am Coll Surg. May 1, 2019.

Landman MP, Shelton J, Kauffmann RM, Dattilo JB. Guidelines for maintaining a professional compass in the era of social networking. J Surg Educ. 2010 Nov-Dec;67(6):381-6.

- Treat all online communication as public

- Patient privacy is paramount.

- Respect intellectual property rights at all times.

- Remember that physicians retain their identity as medical professionals on Social Media.

- Consider the effect of posts on physician-patient relationships.

- Follow the rules.

- Do not exceed authority.

- Be transparent.

- Exercise common sense.

- Recognize that deleting a post from Social Media does not necessarily erase it, even if it is no longer visible on the screen.

The management of perforated duodenal ulcers: operative vs non-operative?

Chung KT, Shelat VG. Perforated peptic ulcer – an update. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2017 Jan 27;9(1):1-12. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v9.i1.1.

Mortality is a serious complication in PPU. As we mentioned before, PPU carries a mortality ranging from 1.3% to 20%[9,10]. Other studies have also reported 30-d mortality rate reaching 20% and 90-d mortality rate of up to 30%[11,12].

Significant risk factors that lead to death are presence of shock at admission, co-morbidities, resection surgery, female, elderly patients, a delay presentation of more than 24 h, metabolic acidosis, acute renal failure, hypoalbuminemia, being underweight and smokers[11,127-131]. The mortality rate is as high as 12%-47% in elderly patients undergoing PPU surgery[132-134]. Patients older than 65 year-old were associated with higher mortality rate when compared to younger patients (37.7% vs 1.4%)[131]. A study involving 96 patients with PPU also showed that there was a ninefold increase in postoperative complications in patients with comorbidities[119]. In another large population study, patients with diabetes had significantly increased 30-day mortality from PPU[135]. (Chung, 2017, p. 8)

Stoma versus stent as a bridge to surgery for obstructive colon cancer

Veld JV, et al. Changes in Management of Left-Sided Obstructive Colon Cancer: National Practice and Guideline Implementation. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019 Dec;17(12):1512-1520.

Results: A total of 2,587 patients were included (2,013 ER, 345 DS, and 229 SEMS). A trend was observed in reversal of ER (decrease from 86.2% to 69.6%) and SEMS (increase from 1.3% to 7.8%) after 2014, with an ongoing increase in DS (from 5.2% in 2009 to 22.7% in 2016). DS after 2014 was associated with more laparoscopic resections (66.0% vs 35.5%; P<.001) and more 2-stage procedures (41.5% vs 28.6%; P=.01) with fewer permanent stomas (14.7% vs 29.5%; P=.005). Overall, more laparoscopic resections (25.4% vs 13.2%; P<.001) and shorter total hospital stays (14 vs 15 days; P<.001) were observed after 2014. However, similar rates of primary anastomosis (48.7% vs 48.6%; P=.961), 90-day complications (40.4% vs 37.9%; P=.254), and 90-day mortality (6.5% vs 7.0%; P=.635) were observed.

CONCLUSIONS: Guideline revision resulted in a notable change from ER to BTS for LSOCC. This was accompanied by an increased rate of laparoscopic resections, more 2-stage procedures with a decreased permanent stoma rate in patients receiving DS as BTS, and a shorter total hospital stay. However, overall 90-day complication and mortality rates remained relatively high.